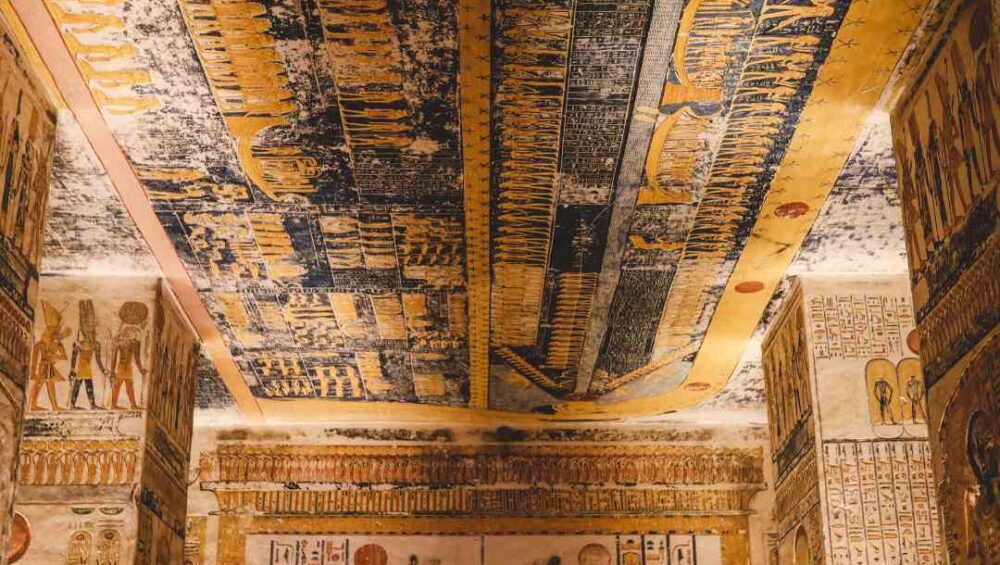

Deep in the limestone hills of Luxor, on the west bank of the Nile, stands the Valley of the Kings, the renowned royal necropolis of the New Kingdom. Here, the kings of the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties chose their eternal resting places, ensuring their legacies endured for millennia.

Historical Significance

The Valley of the Kings, locally known as el-Qurn (meaning “the Horn”), boasts an evocative pyramid-shaped peak that likely influenced its selection as a site for royal burials. The valley branches into two wadis: the main branch forms the primary valley, while the secondary branch, the Western Valley, houses the tombs of only two known kings, Amenhotep III (WV22) and Ay (WV23).

Tombs and Discoveries

The necropolis contains sixty-two tombs. Thutmose I (1504-1492 BC) created the earliest, KV38, and Ramesses XI (1099-1069 BC) built the latest, KV4. Despite its name, the Valley of the Kings does not exclusively contain royal tombs. Out of the 63 tombs, only 20 are royal, while the rest belong to nobles and the wives of kings.

KV63: The Last Discovery

In 2005, archaeologists discovered KV63. Initially thought to be a tomb, it was later identified as a storage site for mummification tools. Located a few meters from Tutankhamun’s tomb, it contained seven coffins, all empty except for mummification implements, dating back to the 18th dynasty.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb

The most famous tomb in the valley is Tutankhamun’s (KV62). Howard Carter discovered it on November 4, 1922. It remains the only intact tomb, spared from ancient robbers primarily due to its location beneath the tomb of Ramesses VI. Tutankhamun, known as the “Golden King,” ruled Egypt for approximately ten years, dying young at around 19 years old. Most of his treasures are now displayed in the Cairo Museum.

The Tombs and Their Robbers

Despite efforts to conceal the tombs, robbers eventually plundered all except Tutankhamun’s. Documents and papyrus records from the 18th dynasty reveal that robbers targeted the tombs of pharaohs, including Ramesses VI. During the reign of Ramesses IX, priests hid the mummies of Amenhotep I and II and later relocated most mummies to a deep shaft near the Deir el-Bahri temple, known as the Deir el-Bahri Cache.

Visiting the Valley of the Kings

Visitors can access several tombs in the Valley of the Kings, including those of Ramesses III, Merenptah, Ramesses IV, Tawosret and Sethnakht, Ramesses IX, Ramesses VII, Seti II, Siptah, and Thutmose IV. Notably, the tombs of Tutankhamun and Ramesses VI require an extra ticket. Admission typically includes access to three tombs, and the use of cameras and video equipment is prohibited to preserve the tombs’ colors.

Deep in the limestone hills northwest of Deir el-Bahri, the Valley of the Kings stands as a testament to the grandeur and ambition of the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt. From the earliest tomb of Thutmose I to the last resting place of Ramesses XI, this valley has witnessed the rise and fall of some of Egypt’s most powerful rulers. Although many tombs were looted, the Valley of the Kings remains a profound symbol of the ancient Egyptian belief in the afterlife and the enduring legacy of its kings.